Clayton Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma argues that great companies stumble not because they can’t innovate, but because they protect their profitable incumbents too long. Diabetes care is a live case study—and Eli Lilly is the rare incumbent choosing to disrupt itself.

For a century, insulin has been a dependable franchise. Along with Novo Nordisk and Sanofi, Lilly dominates global insulin, a market historically controlled by this triopoly. Protecting that base would be the “rational” choice for a quarterly-driven system. Yet Lilly leaned into incretin therapies—drugs that, by design, can reduce or delay the need for insulin in Type 2 diabetes. That’s textbook cannibalization. And they did it anyway.

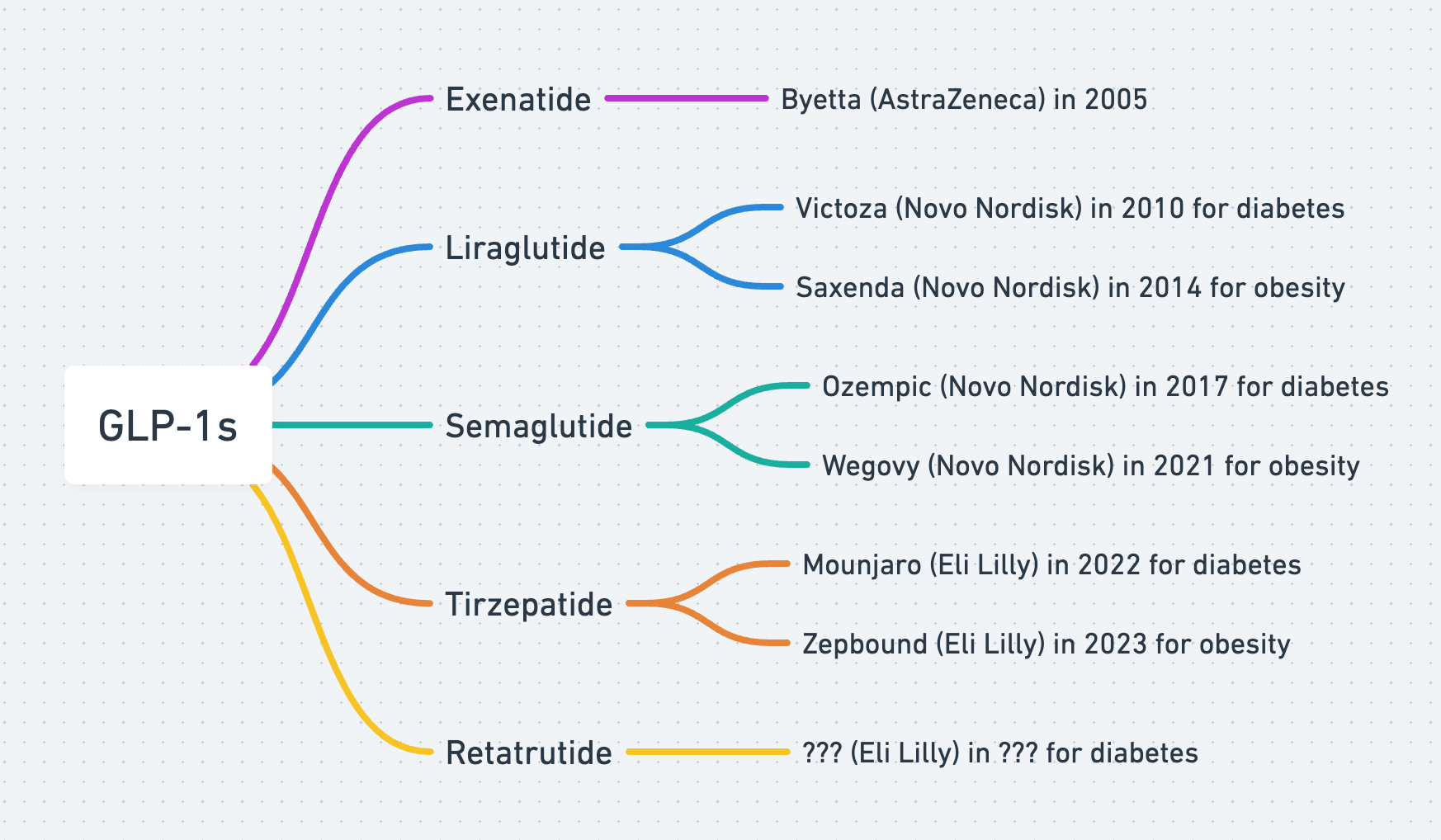

The pivot centered on tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 agonist. Lilly first launched it as Mounjaro for Type 2 diabetes, winning FDA approval in 2022. One year later, tirzepatide won a second label as Zepbound for chronic weight management, opening the much larger obesity market. In other words: the same molecule began eating into parts of Lilly’s own insulin demand curve while creating a bigger S-curve of growth. That’s deliberate self-disruption at enterprise scale.

Critically, Lilly didn’t stop at injectables. The next act is oral meds. Orforglipron, a once-daily, non-peptide oral GLP-1, has produced positive Phase 3 results and could broaden access through simpler distribution and potentially lower costs. If injectables dented insulin, orals can dent injectables. Again: choose to cannibalize yourself before someone else does.

And there’s even a third lane: going beyond GLP-1. Retatrutide, a triple-agonist (GLP-1/GIP/glucagon), has shown striking early weight-loss data in peer-reviewed research, suggesting still more efficacy headroom. If successful, it won’t just cannibalize insulin; it could cannibalize first-gen GLP-1s as well. That is the point.

Zoom out and the lesson is simple. The innovator’s dilemma tempts leaders to delay the hard move because cannibalization feels like self-harm. Insulin remains essential, especially for Type 1 and later-stage disease. Yet for earlier Type 2 and for obesity, incretins are resetting the standard of care. Lilly made the uncomfortable choice to follow the science, even at the expense of its cash cow. That cultural decision—accept near-term cannibalization to capture the next S-curve—now looks obvious in hindsight. It rarely does in the boardroom.

The paradox of disruption is that the fastest way to protect a franchise is to be willing to obsolete it. In diabetes and obesity, Lilly is showing how to do it: build the better product, ship it, scale manufacturing, and let your old business be your first and best customer to lose.